New Perspectives

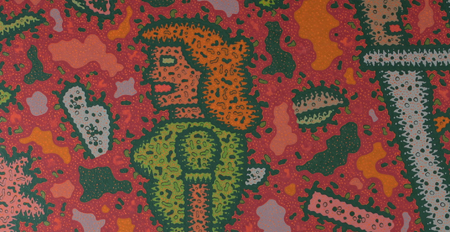

Roger Brown

and the American Scene

by James Yood

It’s pretty much impossible to drive from one side of America to the other without crossing one of the several spectacular mountain ranges that, roughly speaking, cross our nation from north to south. And while we motor through our “purple mountains majesty, above the fruited plain” we encounter amidst the upbeat notices—SCENIC OVERLOOK AHEAD, WELCOME TO COLORADO!--more cautionary yellow warning signs that, in all capital letters, inform us: TRUCKS USE LOW GEAR, TRUCKS CHECK BRAKES, STEEP GRADES AHEAD (could be a tough college), HAIRPIN TURN, or my personal favorite, RUNAWAY TRUCK RAMP.

The similarly bright yellow graphic image that accompanies these signs is almost always comprised of a black isosceles right triangle with its slope side set at around 45 degrees, with a black silhouette of a truck shown heading (careening?) downward, often with a terse smaller panel noting that this scenario is likely to hold for the next ‘x’ miles. There, amidst some of the most riveting scenery America can offer, is the reminder that danger, destruction and catastrophe ride alongside you, that trucks and trailers and those that drive them face hair-trigger life-and-death challenges updating those faced by the pioneers and Native Americans who first crossed those mountains centuries ago.

Roger Brown (1941-1997) came from the hill country of northern Alabama (he’s from Hamilton, about 45 miles east of Tupelo; Brown claimed a distant cousinship with Elvis Presley) and was certainly no mountain man. He spent the great part of his adult life in the almost hypnotically horizontal flatlands of the Midwest, working in and near Chicago. But in the great American tradition of wanderlust by automobile, Brown loved to travel and crisscrossed the nation numerous times, driving (among his prized possessions was a 1968 black Ford Mustang) from Chicago to one or the other coasts in 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975 (the year he painted Jacknife; he also lived in Albuquerque that year for two months), 1977, 1979, 1982, 1983 and 1986, and almost certainly other times as well.

Those trips began and ended in Chicago, where Brown arrived in 1962, eventually attending the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and receiving his BFA in 1968 and MFA in 1970. There, working particularly with Professor Ray Yoshida (represented by a fine painting in the Hallmark Art Collection) and a group of energetic young colleagues, Brown began the path that would lead him to a stellar career and a great presence in the art movement known as Chicago Imagism. As Jacknife indicates, Brown manifested and helped to articulate many of the major tendencies of Imagism—a predilection for symmetry to organize the composition, a wry sense of humor often rooted in vernacular culture, fastidious execution that denies and/or obscures any trace of its creation (no painterly effects or visible brushwork, no ‘happy accidents’ in the process of painting, everything predetermined, etc.), a strong sense of pattern that conflates 2D and 3D realms, relatively modest scale (as distinct from the art of New York), a commitment to the human figure and human narrative (as opposed to abstraction), a kind of blue collar take on mass culture, the lifelong retention of a personal and idiosyncratic style and the sense of an art piece as a scrupulously crafted object, in the case of Jacknife combining painting and sculptural elements. Brown, more than most of his Imagist colleagues (including artists such as Ed Paschke, Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, Philip Hanson, Karl Wirsum, Barbara Rossi, Christina Ramberg, Ray Yoshida, etc.) enjoyed a playful and, in his way, an almost moralizing and didactic sense of storytelling, and his work can be seen as comprised of clever narrative playlets, a kind of witty (and sometimes rueful or caustic) observation on the full range of the human comedy.

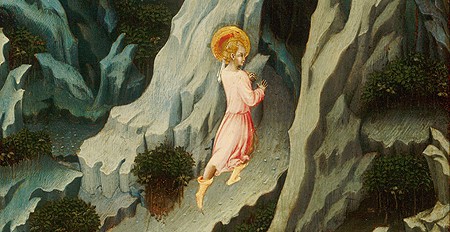

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago is, of course, affiliated with one of America’s great art museums, and when Brown was a student many of his classes were held in and around its terrific collections. Just as the Hallmark Art Collection’s Ray Yoshida’s 1983 False Front exhibits his long and close study of the AIC’s masterpiece, Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, Brown too spent many hours combing the AIC collection. The AIC’s Saint John the Baptist Entering the Wilderness, one of six panels by Siena-based Renaissance artist Giovanni di Paolo on that saint’s life, painted between 1455 and 1460, became somewhat of a touchstone for Brown throughout his career. He responded avidly to Giovanni’s and, for that matter, Siena’s tradition of difference and independence from the more rational and mathematically derived perspective and spatial schemes of nearby Florence. Brown delighted in how Giovanni retained a kind of medieval and courtly flavor with his repetition of the Saint John figure twice in the same space with no diminution of scale, his zigzag patterning of the path he ascends between two mini-mountains, the extremely high horizon line of this very tilted landscape and the charming and naive fable-like quality of the entire ensemble. All are echoed in Jacknife; if anything, Brown is even more committed to a strict symmetrical pattern formula than Giovanni was, with his snake-like road rhythmically winding its way through repetitive bookend foothills squeezed between framing mountains.

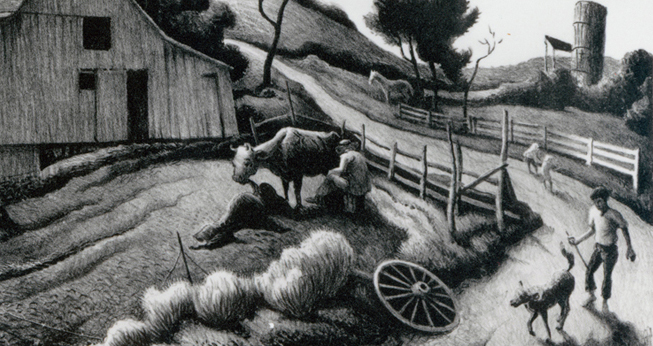

But, of course, Brown is not depicting events from the life of a saint. Rather, he has constructed a rather hieratic scene to suggest something more akin to a secular drama, to condense a little snippet of the reality of the American scene to an essence, to treat, in effect, a genre scene with the trappings of a religious and moralizing image. Brown took great pride in his place as a Midwestern artist, embracing the reality of working in Chicago at a time when New York was in complete cultural ascendency, almost defensively taking up the gauntlet of having the voice of his place, his region, still be heard. In his 1981 Giotto and His Friends: Getting Even Brown allegorically compared the position of Chicago and New York artists with those of Renaissance Siena and Florence, identifying artists such as himself (and, for his time, Giovanni di Paolo) as misinterpreted and, due to the realpolitik of American culture, denied the full acknowledgement of their vision. Brown often in his work hearkened back to the great American Regionalist generation of the 1930s, seeing in artists such as Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton—both, like Brown, alums of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—an ability to examine and articulate the grand American dramas taking place between the coasts.[1] Brown never ran out of things to say about those dramas, and, for example, between 1974-77 created paintings that took as their subjects the assassination of JFK, soil erosion, Nixon’s visit to the Great Wall of China, Canadian seal hunts, Evel Knievel’s Snake River Canyon spectacle, urban sprawl, Civil Defense warnings of nuclear attack and Jacknife.

Trucks and their drivers had become, after all, a bit of a mainstream craze in the mid 1970s. C. W. McCall’s crossover country hit “Convoy” made a big splash in 1975, with the Sam Peckinpah film derived from it coming out in 1978, and Burt Reynolds’ Smokey and the Bandit series usually had a subplot about truckers. The CB radios that nearly all truckers started carrying changed truck driving from a sleep-deprived, amphetamine enhanced, lonely isolated job performed by rugged individualists to becoming seen as part of a fellowship, a community, and one seemingly obsessed about collaboratively circumventing state troopers and weight scales. The open highway meant freedom, with the long-haul truck driver a road warrior in a blue-collar army of servants of commerce whose livelihood rested in that at any moment there are 12 tons of goods in Atlanta that need to be in Sacramento in a day or two, and a truck is a good way of getting that done.

That is, if that truck can safely get over a mountain range or two. Brown, on his regular cross-country driving trips undoubtedly shared the experience that many of us have witnessed, that of innumerable trucks lumbering up a mountain, moving like awkward behemoths, exuding noise and smoke and squealing groans of effort, reminiscent of Sisyphus rolling that rock uphill. And then the summit is reached, and the laws of gravity and physics take over, and suddenly the behemoth seems as light as a feather. The struggle turns into a delicate and lithe dance, with incredible finesse and skill required to control a truck that wants to accelerate more than it should, as if its freedom of descent is the reward for its labor of ascent. Some 80,000 pounds of truck, trailer and driver (that’s the legal weight limit for a truck in most states, though a few mountain passages set a limit closer to 60,000 pounds) here illustrate why, according to the US Department of Labor, truck driving is the single most hazardous occupation in America, producing about 1,000 fatalities yearly amidst its near 500,000 vehicular accidents.

One of those accidents is depicted in Brown’s Jacknife, though this time everyone walks away alive. It’s an American Scene image, not a tragedy, almost more akin to one of those cautionary public service posters warning of bad behavior as a way of encouraging better, and one could imagine this work being posted as a cautionary tale at truck stops and the like. In it Brown shows his main character, a descending truck, three times, with no perspectival diminution of scale and one change of medium from painting to sculpture. In the cab of the truck are two figures rendered in a device that Brown employed continuously for about 30 years, solid black silhouettes of forms that turned figures into signs. While Brown in so doing always successfully indicates gender, he denies specific individual personhood; his men and women are characters, everyman and everywoman. In the 2D painted truck we see the woman in the vehicle’s cab (and this would be rare in 1975; while cross country truckers sometimes worked in teams so one could drive while the other rested, it was unusual for women to be employed in this industry at that time) gesticulating wildly, indicating that the truck is out of control. But at the bottom of Jacknife we see that all’s well that could have ended worse; the truckers safely stare from their now unhinged cab, joined by what seems to be a highway patrol officer, their cargo container lying on its back some distance below, now transformed into sculpture. (Brown dabbled in a sort of folksy sculpture on and off his entire career, and especially often in the 1970s; most of these are small in scale, as in Jacknife, and for him another way that an artist could function as a skilled craftsman. He returned to the device of attaching a ledge to hold objects at the bottom on his canvases in his final years, in his Virtual Still Life series.)

Jacknife is signature Roger Brown: a highly stylized and tautly controlled narrative vignette culled from his ruminations on an event he witnessed, pondered upon and, with great pictorial discipline, then transformed into a universal parable on the follies of humankind. Brown would often examine in his work the helplessness of humans and the fragility of their creations and desires set against the power of nature, hearkening back to the powerful apocalyptic narratives he heard in church growing up in Alabama (before moving to Chicago, Brown considered becoming a fundamentalist preacher, and began studies toward that end). In Jacknife we see what happens when humankind uses its will and its technology—the interstate highway system, enormous trucks and trained truckers engaged in commerce—and pits them against the spectacle of nature. Not only does the mountain sometimes win, in Brown’s witty but sober cosmology it’s unlikely ever to turn out any other way.

More information about Jacknife can be found here.

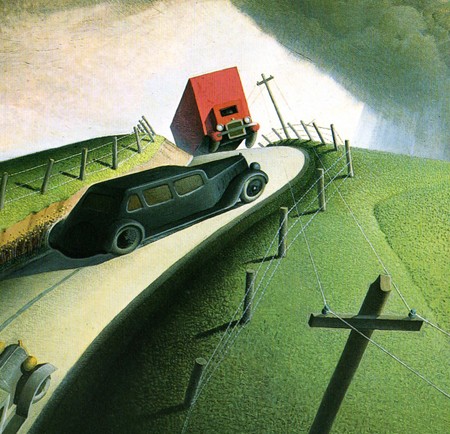

[1] Roger Brown was particularly drawn to the work of Grant Wood and cited Wood’s 1935 Death on the Ridge Road as one of his favorites. It likely served as a prototype for Jacknife, with a similar careening boxy truck, a curvy road snaking through the middle of a stark and isolated landscape, the almost hypnotically repetitive fence posts lining the road, and the horizon line, but with a different outcome. Where Wood saw death in store for the driver in the snappy sedan who decided to pass an old roadster, Brown concentrates on the truckers–whom he decides to spare–and creates more of a stylized fable than a depiction of an actual event.